2014-06-12 Didcot

A Tale of Kings and Castles

and many other types of steam locomotives at Didcot Railway Centre

and many other types of steam locomotives at Didcot Railway Centre

1 During my 2014 UK holiday I insisted on visiting the Didcot Railway Centre. I visited it in 2009 but it was raining pretty seriously then, and I wanted to do this fantastic site justice by returning here in good weather. To the best of my knowledge, but by all means correct me if I'm wrong, Didcot is home to the largest collection of King and Castle Classes. Didcot's landmark building is its coaling stage |

2 An aerial view of the center with the southern half on the right (take the turntable as an orientation point). Note: where my camera's GPS could get a fix on satelites the coordinates can be found below this caption. Click on "See map" to see the corresponding, errrm, well, um, map! It will open in a separate window. Please do appreciate that a consumer GPS is not too accurate especially when near or in buildings. Also bear in mind that it locates the position of the camera and not that of the object on the photo. |

3 This is the sight a visitor gets when (s)he enters via the station. |

4 In the engine shed was my first target. The sun was out so I might be lucky and make some decent photos of the recently restored King Edward II. |

5 Well, I was extremely lucky. Photography in a shed is very difficult with dim and dull lighting conditions and usually very cramped spaces. I found the King to be perfectly lighted and in a free position from at least the right hand side. |

6 |

7 Too big to fit even in my 10mm wide angle lens I had to revert to this panorama photo |

8 Yes, a selfie with a King!!! |

9 King Edward II is a special story in the land of preservationists. Its rear wheel was damaged beyong repair in the scrapyard. It was therefore considered that this loco could never be restored. Casting new wheels was considered impossible at that time. Despite all the odds a new wheelset was made, and "re-inventing" the casting process opened up the road for many other initiatives. Today even complete new locomotives are being built. |

10 The same King Edward II at Woodhams' Scrapyard, in 1982. Clearly visible is the damaged (cut up?) rear driving wheel. Image from Wikipedia under Creative Commons license |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 Built between 1927 and 1936, these engines were the pinnacle of GWR locomotive development. Part of the design background was the desire to regain the title of having the "most powerful express passenger steam locomotive in Britain". They were witdrawn in 1962, three made it into preservation. |

15 The King is a four cylinder class. The valve gear timing of the outside cylinders is derived from the inside motion via this lever. |

16 Another typical feature of the King is that the front running axle has outside bearings ... |

17 ...and the second inside bearings. |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 I'm not sure but I think this is a cylinder blow valve. There is a same appliance in the back of the cylinder (see two photos back) which strengthens this thought. This valve is then intended to blow when the cylinder pressure exceeds the maximum operating pressure. |

22 Cylinder drain valves are opened at start up of the locomotive to heat up the cylinder and blow out any condensation water. |

23 |

24 |

25 Despite its size there is precious little space for its appliances as these "grow" correspondingly. This seems to be the injector that presses feedwater into the boiler. |

26 Turing to the rest of the shed, there is a treasure of GWR locomotives out here. |

27 The Hall is a far lighter engine than the King class. It was far more ubiquitous with 259 members built between 1928 and 1943. Unlike the King this is "only" a two cylinder locomotive. Yet it shares many of the design cahracteristics and standard components that can be found on Kings and Castles alike. Eleven examples of the Hall class have survived to preservation |

28 |

29 Built at Swindon in 1931 as the 101st of its class. Withdrawn 1963. Its rescue by the Great Western Society followed in 1971. It is currently on static display awaiting overhaul. |

30 |

31 Outside there was some shunting with a locomotive under reconstruction. This is what looks very much a newbuilt tender. |

32 Lady of Legend is an example of the Saint Class. None of this class survived the scrapper's torch, the last member being withdrawn as early as 1953. So at Didcot this new Saint is being recreated from Hall class number 4942 Maindy Hall. Find out more at The Saint Project |

33 |

34 |

35 It needs the sacrifice of a Hall class but it recreates a class lost. Is it worth the trouble. How far do you go. How many classes have been lost completely? I wonder. It left me musing. |

36 |

37 After my involvement with this Lady I reentered the engine shed |

38 and saw a Castle simmering in the sun. |

39 No 5051 Drysllwyn Castle is one of eight Castles still in existence. 171 were built between 1923-1950. Like its more powerful sisters of the King class it has a four cylinder design but with a lighter axle load and a substantially lower tractive effort. They were nevertheless formidable machines capable of reaching 160 km/h |

40 |

41 |

42 |

43 Directly in line behind the Castle is no 6998 Burton Agnes Hall. This locomotive was built for British Railways to GWR specifications at Swindon in 1949. The original GWR Hall class counted 259 members, numbered 4900–4999, 5900–5999 and 6900–6958, built between 1928-1943. Upon formation of the British Railways locomotive construction was at first continued on the basis of well-established designs. No 6998 was a member of the 71 strong Modified Hall class built from 1948-1950 |

44 The Modified Hall class was shortlived, the oldest of the class barely getting over 20 years of service. |

45 Not all GWR locomotives were BIG. This relatively modest 2-6-2 prairie engine was designed for small mixed traffic branch working |

46 100 were built from 1927 to 1929 |

47 And this one is awaiting overhaul |

48 I took a final shot in the shed and went out into the sun for something to eat, to sit and enjoy the place and most of all: explore the rest of the site. |

49 A chimney for a locomotive with a single blastpipe. The blastpipe uses spent steam blasting it across the smokebox through the chimney. On doing so it creates a partial vacuum that sucks the hot gases from the firebox through the boiler tubes, creating the draft for the fire to burn and heat the boiler. The better the vacuum the better the fire burns. |

50 But a blastpipe also creates a backpressure on the cylinders. The higher the backpressure, the less effective the locomotive will perform. A simple means to reduce the backpressure is using two blastpipes and consequently a double chimey. |

51 Shop and refreshment area |

52 |

53 Behind the engine shed there is ample opportunity for photograpic inspiration |

54 |

55 |

56 |

57 |

58 |

59 |

60 This is the front of 4079 Pendennis Castle waiting patiently in the Locomotive Workshop. Normally almost invisible, the two inside cylinders now clearly show. The big holes are the actual cylinders, the top (covered) holes contain the valve pistons that time the steam admission to and exhaust from the cylinders. |

61 |

62 Pendennis Castle has a special story for me in store. The 1924 built loco was withdawn in 1964. She spent some years in English preservation without much success. In 1977 she was sold to Australia and was used for a variety of excursions until expiration of her boiler certificate 1994 . In 2000 she returned to the Didcot Railway centre were she is now gradually being restored. Now comes the odd part. While I was in Didcot in the engine shed I was addressed by an Englishman who asked if I could explain something about the workings of the steam locomotive pointing at the King Edward II. During the conversation that ensued it turned out that his company was an Australian who used to fire the engine while she was Down Under! He was disappointed to find her still in pieces here, but nevertheless it was a bolt of coincidence to stumble over that man! I hope he reads this story. |

63 |

64 |

65 There is a lot more work to do in this shed |

66 |

67 |

68 |

69 |

70 |

71 |

72 |

73 |

74 |

75 I gradually moved towards my second objective of the day: seeing the steam motor railcar no 93, recently restored to full working condition. |

76 |

77 |

78 |

79 |

80 |

81 |

82 |

83 |

84 |

85 |

86 |

87 |

88 The oddest of traversers I have seen so far. |

89 |

90 There is at long last, GWR steam railmotor no 93, one of very few (three?) operational steam railmotors in Europe. This railcar has one normal unpowered bogie and one steam powered bogie. On their introduction they were a resounding success. See this video |

91 It was not my lucky day though. The railmotor was propped up and its unpowered bogie removed. |

92 As the shed was fenced there was no getting to the motor bogie |

93 |

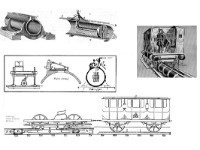

94 In the distance the rodding of the power bogie can be seen. |

95 Next I moved on to the broad gauge part of Didcot |

96 |

97 Before reaching that I found this part. It is a recreated section of Brunel's infamous atmospheric railway. The idea? Quite bright actually. Create a vacuum in a tube and draw a tight fitting piston through it. Attach a train to the piston and tada, you have a train without a locomotive. Bright idea, BUT..... |

98 ...it didn't work out. Keeping the tubes vacuum was too difficult and after only seven months operation ceased. |

99 |

100 These pipes survived as drainage. Sad story. |

101 My third objective for the day |

102 A broad gauge locomotive? Well yes... |

103 ...but not one... |

104 ...but two in one shot. It is widely believed that here in Didcot it is possible to find two broad gauge locomotives along side each other for the first time since the end of broad gauge in England on 20 May 1892. |

105 The track in the middle is dual gauge: standard and broad, enabling you to see the difference. |

106 |

107 |

108 Both locos are replicas |

109 |

110 |

111 |

112 |

113 |

114 |

115 |

116 |

117 |

118 |

119 The locomotive was standing half in the sun half in the shadow making it impossible to make a decent photo. |

120 |

121 |

122 |

123 |

124 |

125 |

126 There were some excursions but apart from that there were very few visitors. |

127 Manual labour |

128 This loco was used for the school excursion train. |

129 |

130 |

131 |

132 |

133 I did a last round in the engine shed. |

134 5900 Hinderton Hall's driver's cab was accessible. My extreme wide angle lens (10mm) was put to good use. |

135 |

136 A view from the firemen's side. Contrary to all other companies GWR was driving right-handed. |

137 And the corresponding driver's view. Note how little the crew could see in front of the locomotive, not much more than the lineside signals. |

138 The driver's tools: the red spindle in the middle is the reverserser, which determines the direction of travel but also the amount of steam that is admitted to the cylinders. At the left is just visible in red and metal the regulator handle. Reverser and regulator determine together how much power is transmitted to the driver wheels. The brass round thing at the left (with the circle of openings) is the brake lever. |

139 |

140 The reverser with in brass the cut-off indication. |

141 What is this bell for? The speedometer is a luxury. That seems odd but in the thirties most locomotives did not have a speedometer. Judging the speed of the train was generally left to the driver’s skill, using his route knowledge and mileposts next to the track. |

142 A view towards the tender |

143 |

144 |

145 A last view on Hinderton Hall |

146 With a heavy heart I left the shed. How long will it be before I return. Will I ever? |

147 After having spent four enjoyable hours in very sunny and nicely warm conditions I finally returned home. In 2009 in pouring rain I promised to return one day in more favourable conditions. A promise fulfilled. |